http://humanvarieties.org/2014/09/21/mhs-book-review-of-deafness-deprivation-and-iq-braden-1994/

And followed by a review of the studies since the book has been published:

http://humanvarieties.org/2014/09/21/the-study-of-deaf-people-since-braden-1994/

Have you read it, and do you think ?

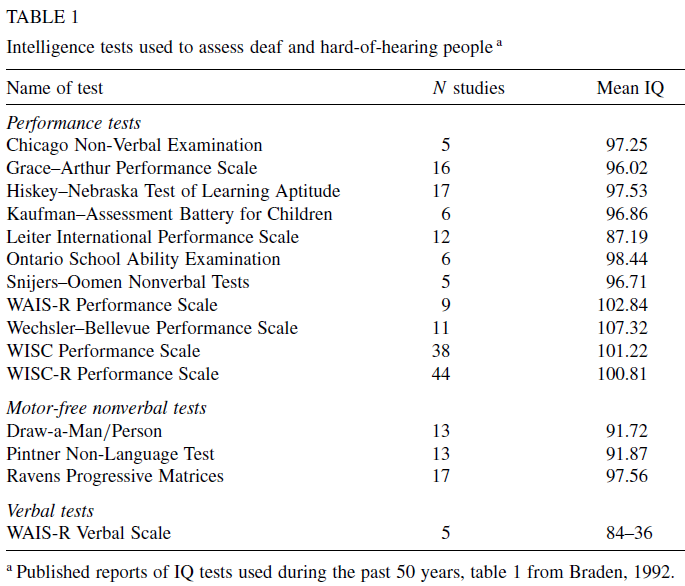

If I have to give a quick summary, I will say that chapters 4 and 5 are very important. You have some evidence that nonverbal IQ is not biased against deaf children and is probably measure invariant, while verbal IQ is not. There is for example no cumulative deficit effects on nonverbal measures, which showed to be robust to cultural deprivation, while verbal IQ is very sensitive (1 SD gap between deaf and hearing groups).

Braden has concluded that nonverbal IQ is not affected by cultural bias, and for this reason, nonverbal IQ is a better approximate of intelligence than is verbal IQ, despite factor analyses showing that verbal tests have higher factor loadings. Although for evidence that Gc and Gf have similar factor loadings, see Ashton & Lee (2006). Regardless, I believe Braden is right, and that cultural theories can't explain group differences in IQ. I don't think even one of them is relevant.

The claim that nonverbal IQ is less culturally loaded, and is a better approximate of g, is interesting, when we think about the Flynn effect, which is much stronger in nonverbal IQ than in verbal IQ tests, even though it is suspected that the Flynn effect is due to environments.

I don't think the Flynn effect contradicts Braden's conclusion that verbal IQ is more subjected to cultural shifts. The causes behind the Flynn effect is not even clear at all. However, we know that the IQ gains have no predictive validity, at least for high-ability persons (see Flynn, 1987, pp. 187-188), and consequently is probably unrelated to intelligence gains. It is, thus, premature to claim it's an environmental effect, especially, if we are unable to detect what are these environments responsible for the Flynn gains.

In particular, there is one kind of studies I would like to see more often. I have written :

Braden next considered the additive and non-additive genetic models. The fact that nonverbal IQ is little affected by large environmental shift implicated in deafness suggests that most variation in nonverbal IQ comes from additive genetic effects (p. 173). Braden (pp. 175-176) cited a study by Paquin (1992) which has directly tested the genetic hypothesis. The correlation between deaf parents and deaf children in nonverbal IQ was close to the predicted relationship of 0.50. Thus, with regard to deaf children with deaf parents, the additive genetic hypothesis is tenable.

The study is dated now, but this is the only one available. That's unfortunate. I think it deserves better attention.